Social and labour activism (and governments’ fear of unrest) were essential forces in establishing modern workers’ compensation systems, including Ontario’s in 1914. The role and response of injured workers in the century that followed have been well documented by the Injured Workers’ History Project.

Injured workers continued to unite to protest shortcomings in benefits and policies. One of the earliest groups, the Brotherhood of Injured Workers, formed following 1932 Middleton Commission’s failure to address the needs of workers already suffering under the Great Depression.

The 1960s – increasing activism

However it was the 1960s and 1970s that saw steady growth of an organized injured workers’ movement. A time of civic activism for social and environmental justice, labour campaigns were also protesting unregulated workplace health hazards and lack of worker rights over their own safety. The post-war recovery had created an automation, construction and mining boom but one which, without adequate legal safeguards, gave rise to increased accidents, injury (especially to the lower back) and occupational disease.

Many also started organizing to protest the way they and their claims were being handled by a hostile, arbitrary – and often discriminatory – Workers’ Compensation Board and its medical consultants. With little access to information and inadequate disability pensions, workers and their families knew that as hard-working, honest employees they deserved better: being treated with respect and dignity, job security or full compensation, annual cost of living increases, the right to diagnosis and treatment by their own doctors, and adequate safety protection.

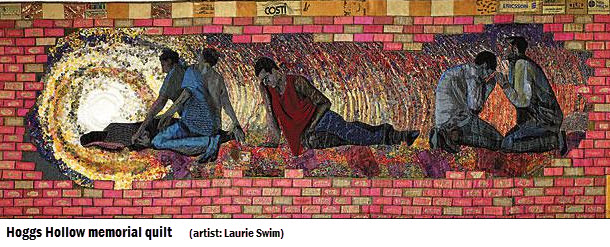

Italian workers, particularly immigrant construction workers who were being injured in disasters such as Toronto’s 1960 Hoggs Hollow tragedy while building Ontario’s roads and cities, formed part of the core of the early injured workers movement, setting up a volunteer organization Association of Pensioners and Injured Workers of Ontario (APIO) . They were joined by progressive law students, some progressive politicians and community legal clinics, in particular, Injured Workers’ Consultants (IWC) and the Industrial Accident Victims Group of Ontario (IAVGO).

Union of Injured Workers and new coalitions

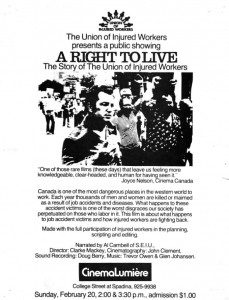

In May 1974 activists combined to form the Union of Injured Workers (UIW) in Toronto under the leadership of Phil Biggin. As part of their organizing, the UIW held education sessions on the WCB, growing quickly over the next five years under the with locals soon added in other cities, until dissent over militancy caused divisions. The proposed law reforms of 1980/1981 recommended by Weiler saw the creation of another coalition in 1981, the Association of Injured Workers’ Groups (AIWG), to organize a united response for progressive reform. Initially including the APIO, Centre for Spanish Speaking Peoples, IAVGO, IWC, UIW and the Committee on the Weiler Study, the group’s criticisms outlined in their submissions and public campaigns were largely adopted by most unions and other community groups, and drew support from some influential politicians. They were able to mobilize injured workers in large enough numbers to force the Conservative government to listen to their concerns in public hearings at Queen’s Park on June 1, 1983 (see the history of Injured Workers Day).

Northern power – and a provincial network (ONIWG)

Although they had prevented government first attempts to replace the permanent disability pension with “wage loss benefits” and deeming, injured worker groups again had to mobilize when the Liberal government reintroduced the dual award scheme in Bill 101 (1984). Their activism succeeded in having it removed from the bill, and in 1985 in winning full cost of living adjustments. Although united opposition was unable to prevent the government’s 1988 Bill 162 from eliminating the pension, it had spurred new coalitions which still lead the struggle for justice today.

A number of new groups formed over the 1980s, including the dynamic Thunder Bay & District Injured Workers Support Group (1984) which, under leader Steve Mantis, encouraged other northern communities to organize also to lobby, provide counselling, education and peer support. Meanwhile community clinic advocates formed the Ontario Legal Clinics’ Workers’ Compensation Network and the Toronto Injured Workers’ Advocacy Group (TIWAG). Following a series of provincial gatherings in Thunder Bay, Sudbury, Niagara, Toronto and Hamilton, 20 injured worker groups in 1991 formed the Ontario Network of Injured Workers Groups (ONIWG) to be an effective voice for province’s injured workers. An early success was pension supplements campaign with labour partners. By 1994 it had 30 members, a representative on the WCB’s Board of Directors, and core funding from the Ministry of Labour.

While reduced cost of living protection under the NDP’s Bill 165 was a disappointment, the injured worker movement regrouped with allies to fight the draconian changes to workers’ compensation of Bill 99 proposed by the Mike Harris and the Conservative Party’s “Common sense revolution”. Although part of the Days of Action in Toronto and coalitions across the province to oppose massive cuts to public programs and social services, injured workers were unable to prevent the cuts to benefits and privatization of vocational rehabilitation services.

But despite losing core funding from government sources, ONIWG and the injured worker movement can claim campaign successes in the following years, including: defeat of the proposal to amalgamate the Appeals Tribunal; recognition of chronic pain by the 2003 Supreme Court of Canada appeal decision in which ONIWG was an intervenor; changes in the Board’s approach to maintenance treatment; reinstatement of the clothing allowance; reconsideration by the Board of its Early and safe return to work policy; reintroduction of cost of living adjustment; and focusing media attention on the perils of experience rating. [For an overview, see ONIWG presentation summary, Feb. 2021]

Collaboration – in person and online

“Austerity measures” and a barrage of cost-cutting policy changes introduced by a new Board administration (2009- ) challenge the movement to find common cause with other groups, such as the disability community and health provider organizations, fighting similar social justice issues surrounding work, health and poverty. Self-advocacy and leadership through initiatives such as the the Injured Worker Speakers Schools and peer support among the community are more essential than ever.

Through its own participatory projects that value lived experiences and joining with academics in initiatives such as RAACWI, the movement continues to back up its advocacy with creditable research – and use social media to gather and share results. Online project tools and videoconferencing remove geographic restrictions on law reform and advocacy collaborations, and expand the reach and impact of injured worker activism and peer support.